PROFESSIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ILLUSTRATION

Valerie Woelfel – St. Paul, MN USA 651 955-7198 – [email protected]

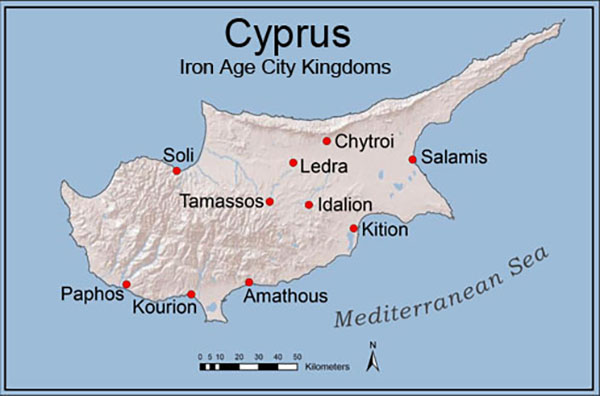

Maps play a crucial role in archaeology where so much information is based on spatial relationships. As an archaeological illustrator I frequently make maps for clients who need to show the locations of sites discussed in a presentation or publication. My background in cartography has given me the skills to understand what to add to a map and what to leave off to clearly communicate with the viewer.

This map, showing the Iron Age kingdoms of Cyprus, strategically uses color to draw attention to the sites while including only minimal background elements to avoid distracting from the main subject. Maps are an essential visual aid in archaeology and I use many of the same techniques with maps that I use to create accurate, attractive illustrations.

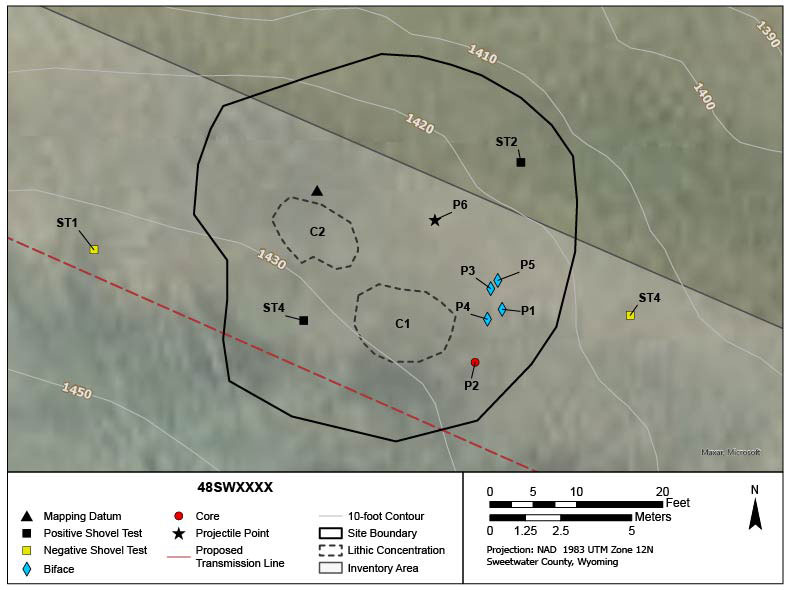

GIS and mapping are vital tools in Cultural Resource Management (CRM, supporting everything from field data collection to spatial analysis and regulatory compliance. In CRM, maps are often created to meet strict government standards, which dictate formatting, symbology, and content for official submissions. While these projects leave little room for creative design, they still require strong cartographic and GIS skills to produce professional-quality maps that provide value to the client.

The example shown here is a sketch map based on field data collection using a tablet. These types of maps help archaeologists document site locations that can have major impact on a client’s project. I have experience as a GIS professional in large environmental consulting firms and understand the demands and deadlines of CRM mapping. I also provide GIS and cartographic support for smaller archaeological firms that many not have a full-time GIS analyst on staff.

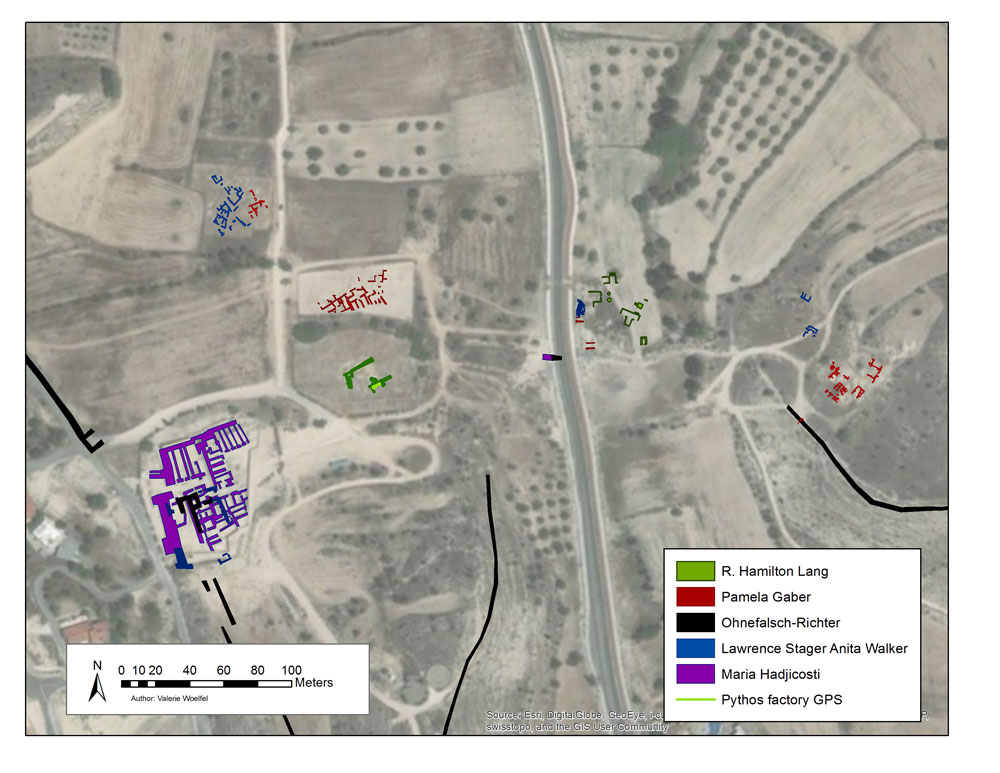

Many archaeologists inherit the maps of earlier excavators to use in their research or to guide their own fieldwork. These maps need to be approached with caution and an understanding of who created them, why they were created, and what tools and techniques were available at the time they were made.

At the site of Idalion on Cyprus, where I serve as assistant director, we have an 1887 map by Edward Carletti, which marks key discoveries and the locations of early excavations going back to the mid 19th century. Fortunately, significant portions of the city walls are visible today and I was able to compare GPS-based mapping with Carletti’s map created with the use of a compass and survey chains. I found that the older map was surprisingly precise. This level of accuracy gave me the confidence to integrate Carletti’s records into our modern GIS and spatial analysis.

Creating effective maps for archaeology requires more than just technical GIS knowledge —it involves a strong foundation in cartographic design principles. I give workshops and talks on cartography for GIS users in archaeology with a focus on how to clearly communicate spatial data through concepts such as color theory, layout design, and the effective use of symbology.

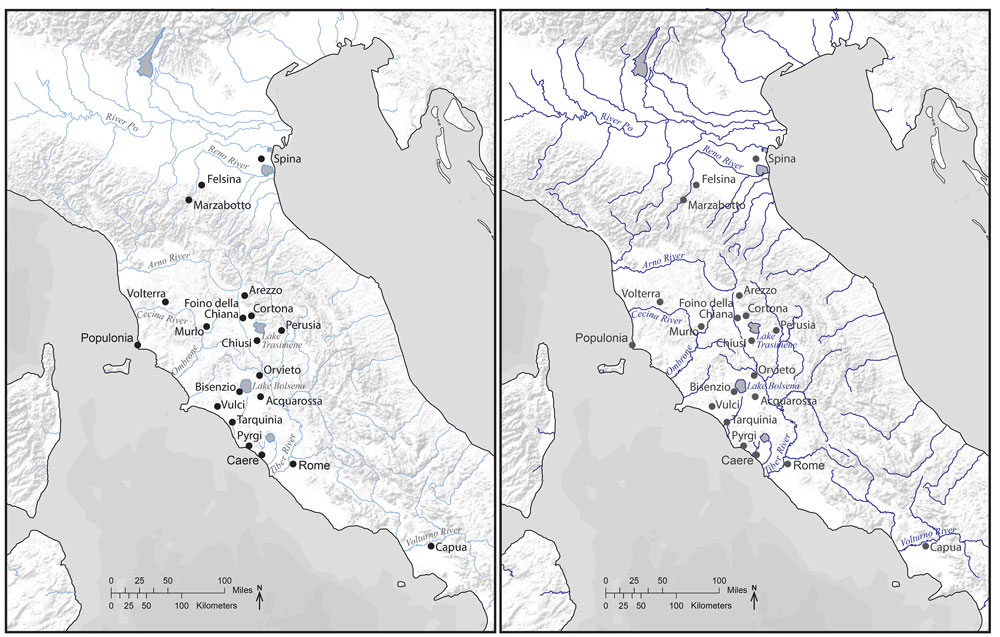

These maps are examples that I use to understand visual hierarchy in cartography. The first is a map of Etruscan sites with rivers in the background; the second is a map of rivers with Etruscan sites in the background. Though they contain the same data, the use of techniques such as larger symbols, stronger colors, or contrast, determines which elements stand out on the map. These visual strategies help guide the viewer’s eye and clarify the map’s primary purpose.

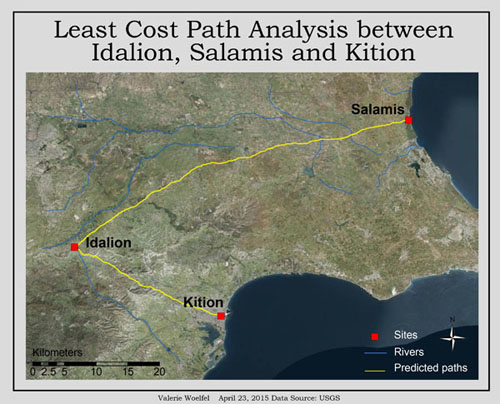

I In addition to creating maps, I have extensive experience performing GIS analysis for archaeological research. This image shows the results of a lease cost path analysis between the inland city of Idalion and the coastal site of Kition on Cyprus. To ensure reliable results in GIS analysis, it is important to understand the methodology and tools used. In this case the least cost path was generated using slope data to model the most energy-efficient route across the terrain.

There is much more to choices in human travel beyond the ease of the route, so this analysis was followed by ground truthing and research into previously located sites along the route. The end result was that some sections of the path could be confirmed while in other others no evidence was found or modern buildings covered the route.